Surprise! You’re the president: A conversation with the first female president of Mauritius

28 Sunday Jun 2015

Posted in Mauritius

28 Sunday Jun 2015

Posted in Mauritius

23 Monday Feb 2015

Posted in Discover Kenya

I loooooove this city! Missing home!

10 Tuesday Feb 2015

Posted in Explore Africa

Botswana earned a reputation for political stability, electoral democracy, and economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s, when much of the African continent appeared to be mired in economic stagnation and authoritarian rule. This reputation has persisted despite contradictory developments. Since the 1990s, many other African countries introduced multiparty elections, and economic performance improved across the continent. Over the same period in Botswana, corruption and mismanagement have become increasingly prevalent while the abuse of governmental authority have drawn attention to the absence of effective checks on executive power.

Many observers – foreign governments, international financial institutions, Freedom House, Transparency International, and academics researchers – tend to downplay these problems. They insist, by and large, that Botswana has remained stable, democratic, and well-governed relative to other African states. The southern African country continues to enjoy “a halo effect”. But the halo has faded. Political tensions are much…

View original post 2,729 more words

10 Tuesday Feb 2015

Posted in Explore Africa

The essential features of Africa’s Growth-Governance Paradox were delineated in 1990 by scholar Jeffrey Herbst. Economic reform programs prescribed by international financial institutions, often called structural adjustment, were premised on reducing the distributional role of the state and maximizing the play of market forces. Herbst noted a contradiction: governing regimes were being encouraged to alter the clientelistic political systems on which their power rested.1

A quarter-century later, sub-Saharan Africa has experienced the most continuous period of economic growth since the 1950s and 1960s. What explains this development: high commodity prices, economic liberalization, better governance and democratization? Some development economists, such as Mushtaq Khan, do not see the necessity of implementing the full “good governance agenda” to achieve a turnaround in economic performance. A theoretical framework, “developmental patrimonialism”, has also been advanced by a group of Africa experts to explain authoritarian modernization in a…

View original post 3,309 more words

17 Saturday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

This is a brief follow up to the link I shared on the status of cancer care in Kenya….. Look at some of the activities being done for cancer care and also screening in a few parts of Kenya by this dedicated group:

16 Friday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

I’m glad this is being discussed!

12 Monday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

05 Monday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

Although we might not always appreciate it, local and national governments have a huge influence over our levels of satisfaction, happiness and general wellbeing. Service delivery – whether in the transport sector, health service or education system – plays a crucial part in our everyday lives. Of course, as with any system, things can and do go wrong. While it perhaps used to be the case that a citizen needed to know which council department or government ministry to write to and then had to hope that their letter would reach a sympathetic ear, mobile and web technology have transformed the ways in which citizens can now interact with their government. Complaints can now be lodged in minutes, rather than weeks. Real-time analytics and feedback platforms can generate almost instantaneous data on the state of service delivery and the numbers of outstanding complaints or issues to be resolved. Such platforms…

View original post 275 more words

03 Saturday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

Wow! Stunned to run in to this hardly an hour after my last blog post on mental health neglect in Africa. Thanks so much TO!

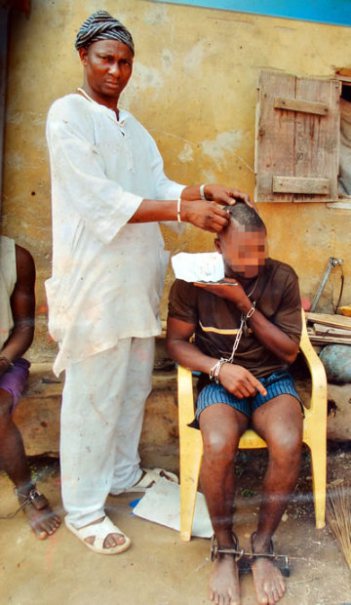

A herbalist at work on one of his patients. Photo: Kunle Falayi

A herbalist at work on one of his patients. Photo: Kunle Falayi

My visit to traditional healers of mental illnesses in Nigeria was really eye-opening. The extent of overhaul needed in Nigeria’s mental health system is simply staggering. I will say the investigation was really eye-opening for me. The fun part was hanging out with those herbalists. Lol

Read here: One psychiatrist, a million patients: Traditional healers take charge of mental cases in Nigeria (II)

02 Friday Jan 2015

Posted in Public Health

Tags

curse, evil machinations, evil spirits, Frank Njenga, Human rights, Human rights based approach, John Kinuthia, Kenya, Locked up and forgotten, Lukoye Atwoli, Mental health, mental health act, mental health policy, Mental illness, post election violence, Poverty, Prejudice, Public financing, Robbin Hammond, Silent epidemic, Stereotypes, stigma, traditional healers, war

“Across Kenya, there’s a terrible secret, hidden from the world. People who barely exist. They live in darkened rooms, if you call it living…they’re Locked Up and Forgotten.” That is an excerpt from a 2011 CNN documentary showing the rot in Kenya’s mental health system. In it we see the inhumane ways in which Kenya’s mentally ill are treated and the degrading conditions in which they are housed. Inpatients at Mathari Hospital Kenya’s main psychiatric hospital were crammed in crowded wards, forcefully medicated and with complaints of sexual abuse from fellow patients going unaddressed. Outside of hospital, the documentary showed how Kenya’s poor struggle to access mental health services. With nowhere left to turn and in a country where stigma and discrimination against the mentally ill or disabled is deeply entrenched, these families result to chaining their ill and hiding them away from the eyes of a society that would rather pretend they don’t exist.

A PBS article; Mentally ill shackled and neglected in Africa’s crisis regions, featuring harrowing images from across Sub Saharan Africa by the photographer Robin Hammond; demonstrates that mistreatment of the mentally ill is widespread in Africa.

Patients chained while undergoing ‘treatment’ at a traditional healer’s in the Niger Delta, Nigeria- Photo by Robin Hammond

The pictures formed the basis of Hammond’s book published in 2014:CONDEMNED – Mental Health in African Countries in Crisis. In the book’s intro, Hammond notes that the mistreatment of the mentally ill in Africa, “was the worst assault on human dignity” he had witnessed in his 12 years of documenting the effects of war and conflict. He further articulates the harsh reality of the mentally ill especially in Africa’s war torn regions:

Abandoned by governments, forgotten by the aid community, neglected and abused by entire societies: Africans with mental illness in regions in crisis are resigned to the dark corners of churches, chained to rusted hospital beds, locked away to live behind the bars of filthy prisons. Some have suffered trauma leading to illness. Others were born with mental disability. In countries where infrastructure has collapsed and mental health professionals have fled, treatment is often the same – a life in chains.

In Africa, the assumption that infectious and parasitic disease constitute the biggest threat to health is erroneous. Poverty, conflict, war, displacement, diseases like HIV/AIDS and tragedies like famine which led Kenya’s psychiatrist Dr. Frank Njenga to call Africa the ‘traumatized continent’ make mental illness a serious concern. Kenya for instance has suffered many traumatic experiences from the Mau Mau concentration camps, post election violence that led to scores of internally displaced persons and several terror attacks like the 2001 bomb blast in the US Embassy in Nairobi and the recent Al Shabaab attack on the Westgate shopping mall.

Unfortunately, the majority of psychiatric problems remain undiagnosed and thus unmanaged in most of Africa. Experts have thus declared mental illness as the continent’s “silent epidemic.” In Kenya for example, mental health experts estimate that 1 in every 4 Kenyans may be suffering from a mental health problem. These range from common disorder like depression and anxiety; severe disorders like psychosis, schizophrenia and bipolar disorders; alcohol and substance abuse problems among others. See:Reforming Kenya’s ailing mental health system for details. Among these conditions, clinical depression is said to be the most prevalent with an estimated 4 million Kenyans suffering from it.

The situation is compounded by the pervasive culture of denial, silence and stigmatization that surrounds mental health issues: Anxiety disorders and depression are seen as Western constructs and therefore Un-African. At best, these are seen as a problem that only afflicts Africa’s middle class. In Africa, depression’s simply NOT A THING-and where it is, one is expected to simply, “snap out of it.” A satirical piece written in the wake of Robin Williams death in Kenya’s Standard newspaper; Depression Has Never Been An African Disease, eloquently captures the trivialization of depression by the Kenyan society. Says the author:

What disturbed me was news that the famed actor (Robin Williams) had committed suicide because he was suffering from depression. What is this depression thing? I accept it when a man hangs himself because his wife has left him, or he is jobless, or the neighbour has bewitched him or he is caught red-handed kissing his mother-in-law. But committing suicide because you are suffering from depression is simply not African.

As a Kenyan who watches NGOs tinkering with jiggered feet, I can’t wrap my mind around the fact that depression is an illness. We are stressed and depressed all the time! In fact, it is such a non-issue that African languages never bothered to create a word for it. Anybody who knows what they call depression in their mother tongue, please step forward.

Depression, I am told, does not have a single cause, but that “an upsetting or stressful life event – such as bereavement, divorce, illness, redundancy and job or money worries” could trigger it. To be honest, some diseases only strike wazungu (white people) or the middle class. Around here, when you are bereaved, you wail your head off, blame a neighbour, slaughter a cow for mourners, get inherited or replace the departed spouse and move on.

An article on the knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of mental illness among staff in general medical facilities in Kenya notes that in many African societies “psychiatric illness is seen as either the outcome of a familial defect or the ‘handiwork of evil machinations’ (demons, evil spirits).” The article notes that such beliefs leads to psychiatric patients being ostracized. The report further notes that “when such beliefs are combined with common stereotypes of the mentally ill as unpredictable and dangerous with a propensity for self harm, harm to others or property leads African societies to stigmatize, fear and shun the mentally ill.”

Mentally ill men and women are imprisoned in Juba Central Prison South Sudan. Photo by Robin Hammond

In the book ‘Mental illness in popular media: Essays on the Representation of Disorders’ the authors note that African communities ascribe mental illness to curses, evil spirits, or witchcraft, “even when mental illness arises from observable and verifiable causes such as drug abuse and sudden changes in lifestyle.” Furthermore, according to the KAP report, most view psychiatric patients as being responsible for their illness, especially when it is an alcohol and/or substance related problem. In Africa, the mentally ill are generally labelled “mad” and the frequent use of of the infamous African proverb “every market has a mad man” in popular media like in this article: Each market has a mad man but Luanda has one too many and the blog, Viva my village madman shows the extent to which society embraces their disdain.

The KAP report notes:

Mental illness stigmatization denies psychiatric patients the empathy and understanding traditionally bestowed on the sick in the African society.”

Ultimately, the silence, negativity and stigmatization that surrounds mental illness in Kenya and Africa at large impedes patients’ treatment. The belief that mental illness has supernatural causes leads many to seek ‘cures’ from the so called ‘witch doctors’ and traditional healers often delaying effective care. The shame attached to the illnesses also means that most would rather suffer in silence rather than seek treatment. Unfortunately, since medical professionals, legislators and policy makers are all drawn from the general population, they share the same prejudice and stigmatizing attitudes as the general public as the KAP article reports. Finally, since most patients are locked away, Hammond notes, “these people are unseen so their suffering is ignored” including by their own governments!

This patient in the Niger Delta, Nigeria, is clearly scared of the traditional healer pictured who claims he can cure him using herbs and prayers while keeping him chained and exposed to the elements. Photo by Robin Hammond

Constraints to the provision of mental health services in Kenya:

CNN’s Locked Up and Forgotten prompted a human rights audit of the mental health system in Kenya by the Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNCHR). The commission’s report: “Silenced Minds; The Systematic Neglect of the Mental Health System in Kenya,” released in November 2011 painted a grim picture of the sub-sector. The report noted that Kenya lacked an effective legal and policy framework for mental health: Kenya’s mental health act which was effected over 25 years ago in 1989 is narrowly focused on inpatient treatment and even then remained only partially enforced because the implementing board of mental health lacked an operational budget.The authors further noted that though a mental health policy was drafted in 2003 and revised in 2007, neither drafts were adopted. Effectively, Kenya has no mental health policy.

The report noted that Kenya’s mental health sector lagged far behind physical health primarily due to gross underfunding by the government. In Kenya, mental health gets just 0.01% of the entire budget allocated to the ministry of health most of which is spent on administrative costs. As a result, Kenya, has approximately 77 consultant psychiatrists, 418 psychiatric nurses and 30 clinical psychologists to serve a population of 44 million. It is also reported that medical students generally frown upon psychiatry making it difficult to raise the number of professionals for the sub-sector.

Also tied to under funding, the report found the available services were of insufficient quality and facilities non conducive to recovery. Inpatient and outpatient services like rehabilitation services and halfway houses are almost unheard of and the supply of psychotropic drugs insufficient. Mental health services were found to be overly centralized with almost 70% of inpatient beds found in the capital Nairobi limiting accessibility. At the time of the audit, far flung areas like the North Eastern province were found to have neither a psychiatrist nor a psychiatric nurse. The report concluded that the legislative, policy, programmatic and budgetary steps the taken by the Kenyan government had been ineffective in realizing the right to mental health and in protecting the right of the mentally ill to have their dignity respected as provided by Kenya’s constitution.

Benefits of a human rights based approach to mental health care:

The KNCHR report concluded that anchoring Kenya’s mental health care in a system of rights would be greatly beneficial since this comes with corresponding state obligations. The report noted that this is important because putting obligations on the government in turn demands accountability; strengthens the ability of poor and vulnerable people to demand and use services and information; prohibits the discrimination and emphasizes equitable access to mental health services. The report was highly optimistic since at the time it was being crafted, Kenya had just promulgated a new constitution (2010).

The authors therefore felt that mental health reform in Kenya was particularly timely at especially since per the new constitution, previously centralized health services would be devolved to 47 newly created counties. Devolving health services should have made mental health access more equitable by making it easier to integrate mental health services in to primary health care and linking this to informal community based services and self care.

But in Kenya, more things change; the more they stay the same:

Why African governments should care about mental health:

As noted in the recent Declaration on mental health in Africa: moving to implementation by global mental health experts, there is urgent need for African governments to address the existing gaps in mental health provision as well as addressing the persisting stigma and social exclusion. Failure to address mental health problems exacerbates poverty because lowers the productivity of individuals and it also curtails the achievement of other health goals. Also as noted by the KNHCR report, “the systemic neglect and marginalization of the mental health sub-sector by governments amount to discrimination against the mentally ill on the grounds of health.” The KNCHR warned that without concrete and targeted reforms in the mental health sub-sector, countries will fail in creating a just, cohesive society with equitable social development.

Bridging the mental health gap is achievable even in low resource settings:

In Improving mental health in Africa, Prof. David Ndetei a leading psychiatrist in Kenya says where resources are a constraint, nations should embed mental health service delivery within preexisting community health delivery services. He notes that Kenya already has many operational community health centers that deliver nutritional interventions and immunizations. He notes that training community health workers working in such centers could improve mental illness screening, treatment and support at the community level. This strategy has been tried and tested in places like India as detailed in the talk: Mental health for all by involving all by Dr. Vikram Patel from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. Dr. Patel believes we can improve mental health delivery in low-resource settings “by teaching ordinary people to deliver basic psychiatric services.”